Circle of Life|Boxing with writers

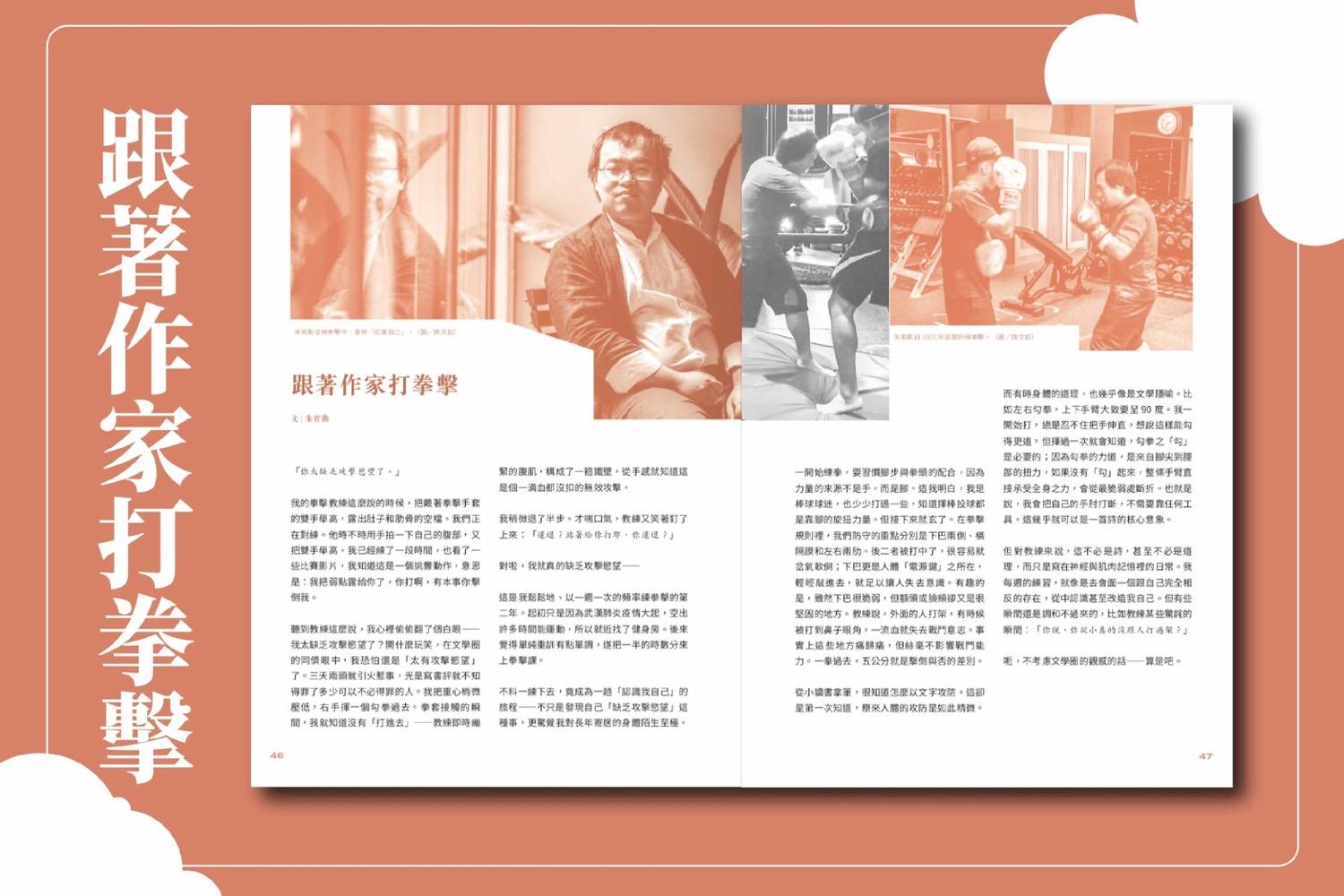

Boxing with writers

Text / Zhu Youxun

"You are sorely lacking the desire to attack."

When my boxing coach said this, he raised his hands with boxing gloves, exposing the gap between his belly and ribs. The two of us were sparring. From time to time, he slapped his own abdomen with his glove and raised his hands again. I have been practicing for a while, and I have watched videos on some matches. I know that is a provocation, meaning: I'm exposing my weakness, so hit me and knock me down, if you can.

Hearing the coach's words, I secretly rolled my eyes in my mind: I lack the desire to attack? Are you kidding me? In the eyes of my peers in the literary circle, I am afraid that my attack instinct is "too aggressive." I often make trouble for myself every two or three days. I can offend God only knows how many people whom I don't really need to offend in just one book review that I write.

I pressed down my center of gravity a little and swung a right uppercut. The moment my glove landed, I knew that I had failed to get inside as my coach had immediately tightened his abdominal muscles, forming a wall of iron. From the feel on my hand, I knew that that was an ineffective attack that drew not a drop of blood.

I took a small step back. I had barely taken a breath when the coach stepped up, smiling, and said, "Backing off? I stand here for you to hit and you're backing off?"

Yes, I really lack the desire to attack—

This is the second year I practice boxing not very seriously once a week. At first, it was just because I had a lot of time to exercise thanks to the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic, so I found a gym nearby. Later, I felt that pure weight training was a bit boring, so I took half of my hours to attend the boxing class.

Little did I expect that as soon as I started practicing, it would become a journey of "knowing myself"—not just to discover things like "I Lack the desire to attack" but also to realize that I am extremely unfamiliar with the body that I have lived in for so many years. As I set out practicing boxing, I needed to get used to the coordination of footsteps and fists because the source of strength is not the hands, but the feet. This much I understand. I am a baseball fan and I have played a little bit, so I know that the swinging of bats and the throwing of balls both depend on the spinning power of the legs. But then it becomes mysterious. In boxing, the focus of our defense is on the sides of the chin, the diaphragm, and the left and right ribs. If the latter two places of a person are hit, it is easy for that person to be out of breath and collapse. The chin is where the human body’s "power button" is located, and a light jab is enough to make people unconscious. Interestingly enough, although the chin is very fragile, the forehead or the cheeks are very sturdy. The coach said that when people outside fight, sometimes the corners of their nose or eyes are hit and bleed. People may lose the will to fight. In fact, though these places, when hit, are painful, they don't diminish in the slightest the person's ability to fight. So, where a punch lands, even if it's just five centimeters apart, may mean the difference between a knocked out or a standing opponent.

I have been studying and holding a pen since childhood. I know how to attack and defend with words, but this is the first time I realize that the offense and defense of the human body are so subtle.

Sometimes the body's reasoning is almost like a literary metaphor. For example, in the left or right uppercuts, the upper and lower arms should form a roughly 90-degree angle. When I first started boxing, I couldn't help stretching my arms straight, believing that my hook could reach farther. But once I had thrown my first punch, I knew that the "hook" was necessary in the uppercuts because the force of the uppercut comes from the torsion force from the toes to the waist. If there is no "hook", the whole arm will directly bear the force of the whole body and the most fragile part will be broken. In other words, I would break my elbow without the help of any tools. This can almost be the core image of a poem.

But for the coach, this does not have to be poetry or even reasoning. It's just a daily routine written in the memory of the nerves and muscles. My weekly practice is like meeting an existence that is a complete opposite of myself and, in the process, I recognize and even transform myself. But some of the moments can't be harmonized, such as moments when the coach was surprised when he said, "You said that you have really never had a fight with anyone since you were a kid?"

Uh, if you don't consider the perception of the literary circle—let's just say that's right.